. Wide-spread vaccine availability, increasing herd immunity, and lower case numbers led to renewed hope and a feeling of normality in 2023. However, especially during the winter seasons and with the potential emergence of new variants of the virus (like Omicron in 2021-2022),

repeatedly becomes a focus for the public. Thus, there is a level of uncertainty about what developments the winter season 2023/2024 might bring.

China showed an unparalleled pace

Cuba's and Japan's coronavirus vaccination campaigns are among the most successful worldwide based on doses per population. In terms of sheer numbers, China and India are the leading nations, with some 3.5 billion and 2.2 billion doses administered, respectively. Since the United Kingdom is no longer part of the European Union, it significantly accelerated its approval processes and

started its vaccination program earlier than most other countries. As a consequence, the UK's vaccination coverage was one of the fastest worldwide.

When it comes to the rate of fully vaccinated persons, there are several countries where more than 80 percent of the population has received the ‘full vaccine package’. Among large countries, China stands out with over 90 percent of its population fully vaccinated, while the U.S. stands at 68 percent. When it comes to the booster shot, which was especially recommended in response to the Omicron variant, Chile was leading among larger countries. At the peak of its vaccination campaign in summer 2021,

China administered millions of doses every day. The daily record was reported for June 28, 2021, with 22.4 million Chinese receiving the vaccine.

Booster campaign driven by Omicron threat

At the end of November 2021, a new variant of SARS CoV-2 was reported in South Africa. Alarming news was that

this variant, soon known as Omicron, showed signs of immune escaping abilities and a so far unseen spreading speed. Somewhat moderating was the fact that the variant seemed not to penetrate deep into the lungs and thus caused a significantly lower rate of severe cases and hospitalizations than

Delta and other variants. Experts, however, quickly emphasized that Omicron’s extreme contagiousness and its evading of immunity could still cause trouble for hospitals and health systems. That was especially dangerous for developed Western countries where demographics show a

much higher share of older populations which are in general more under threat from the coronavirus.

Since many people received their first two shots already five, six, or more months before the new variant appeared,

booster shots for countering the Omicron wave became essential. Studies showed that especially the mRNA vaccines were effective against Omicron, foremost protecting from severe cases. And indeed, although the variant

caused the highest infection numbers since the beginning of the pandemic, death and hospitalization numbers were mostly lower than one year before.

Inequality cast a shadow on the global campaign

Although mathematics tells us that every human worldwide should have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, the reality looks quite different.

Many African countries, but also several countries from Latin America and Southeast Asia, remained white spots on the global vaccination map.

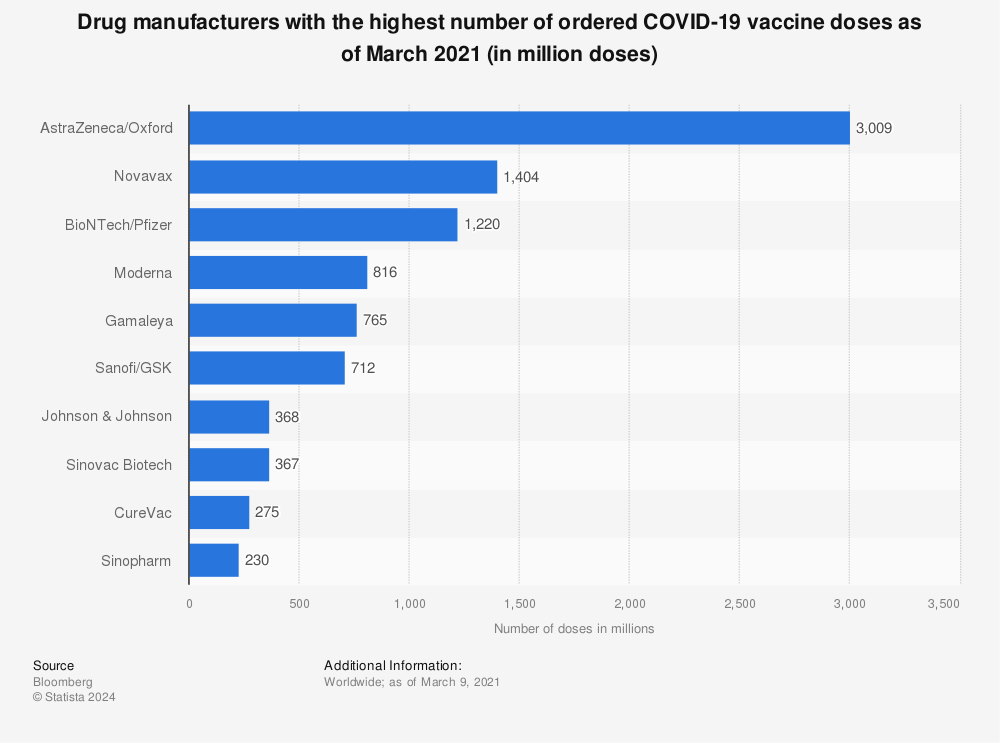

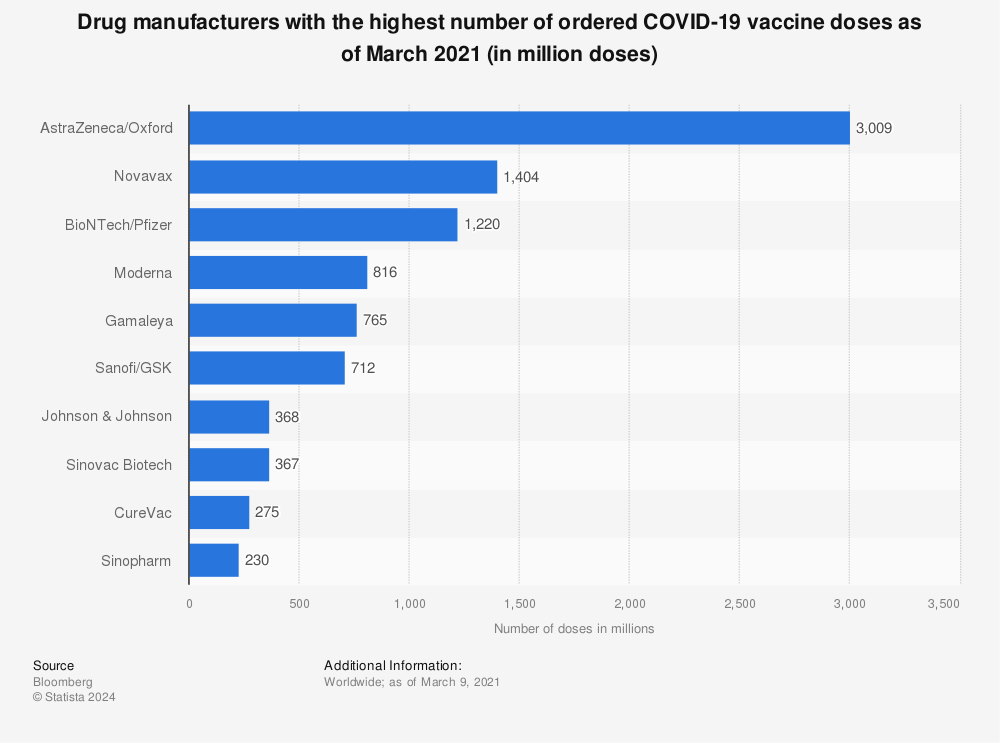

Vaccination inequality became an increasingly prominent key word. It was obvious from the very beginning that rich countries hoarded as many vaccines as they could. Countries like Canada and the UK, for example, reserved doses with which they could vaccinate more than three times their respective population. At the same time, most undeveloped countries were able to secure pre-orders covering only five to ten percent of their population. As of year-end 2022, countries like Haiti, Yemen, and Burundi still had less than three

percent of their population vaccinated.

It is, of course, also up to the biopharmaceutical companies to make their products accessible. While AstraZeneca delivered almost two thirds of its doses to lower-middle-income countries at the height of the vaccination campaign,

Moderna delivered nearly 85 percent of its doses only to the richest countries. In a report, Moderna, Pfizer, and BioNTech were directly criticized by Amnesty International for putting profit before accessibility. These companies have already been criticized in the U.S. and other developed countries for their high vaccine price tags, especially considering the fact that Moderna’s and BioNTech’s COVID-19 research was largely funded by taxpayer money.

Longing for normality

The sudden interest in the vaccines was of course an expression of humanity’s unabated wish to eventually

get back to normal life by reaching some kind of herd immunity. Nothing fueled this hope like the three most prominent/promising vaccines from Biontech/Pfizer, Moderna, and

AstraZeneca/Oxford which started being approved during end-2020. Combined, these three received and agreed to pre-orders for around five billion doses worldwide.

The first COVID-19 vaccine was approved for widespread use

in the United Kingdom, and the first doses were delivered to British seniors on December 8, 2020.

The United States followed, and the first shots were received by Americans on December 14th. Although it was the fastest developed and launched vaccine in human history, a huge obstacle lay ahead: How to distribute the vaccine to billions of people around the world? The largest vaccination campaign ever was also a gigantic supply and logistic challenge.

Trust was essential for a successful campaign

Not only was an effective distribution of the vaccine needed, but also enough people who were willing to get vaccinated.

Vaccine hesitancy has been a problem for many years, and the ongoing pandemic had an intensifying effect. There are countries traditionally skeptical of vaccinations, first and foremost France, Russia, and many other countries of the former Soviet Union and former socialist bloc, as well as regions with strong anti-vaccination movements like Northern Italy. Furthermore, the mixture of a permanent crisis situation, intermittent lockdowns, and restrictions is a breeding ground for general skepticism, rejection of authorities,

and conspiracy theories.

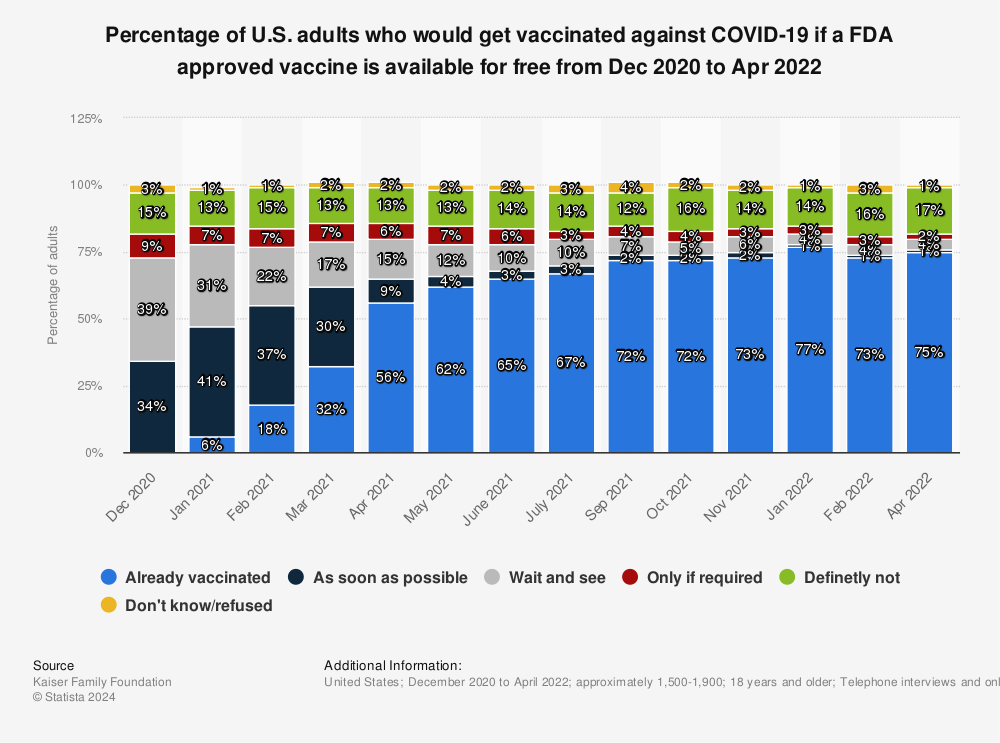

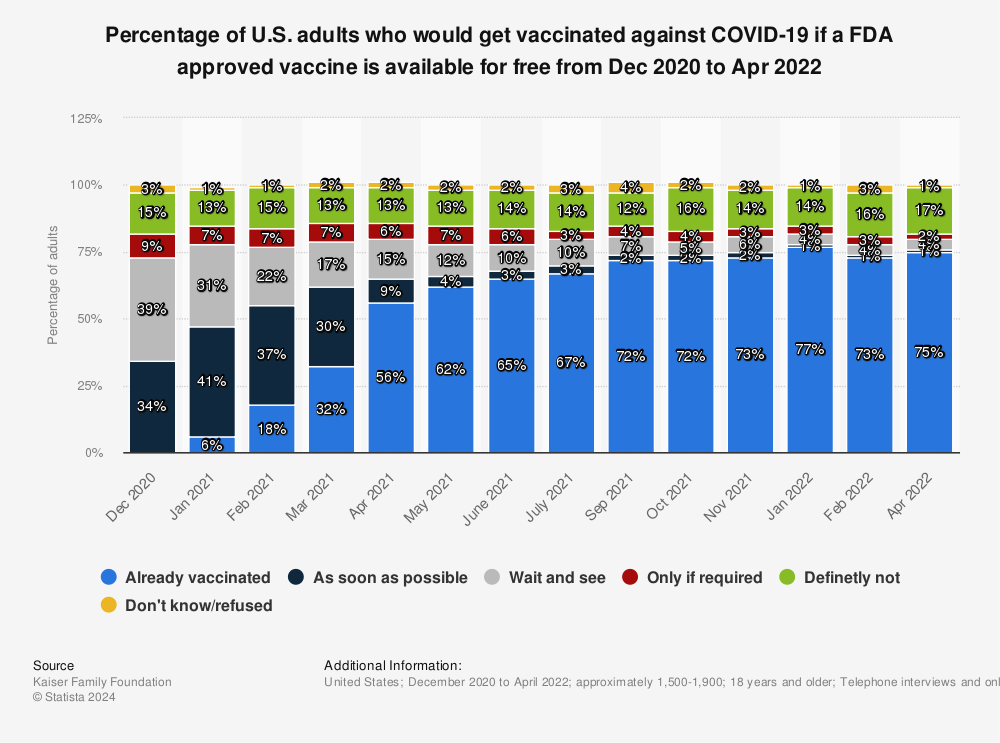

Additionally, the enormous speed with which the laboratories developed

Additionally, the enormous speed with which the laboratories developed and produced the vaccines as well as the quickened process of approval raised concerns among many people, questioning whether they had been thoroughly tested (while other major factors like technology advancements, combined forces in R&D, and the extraordinary funding from many countries were often overlooked).

Accordingly, in many countries the group of hesitant people who ‘first want to wait and see’ was significant – for example, almost 40 percent of all surveyed in the United States at the beginning of the vaccination campaign, although this percentage had decreased to just four percent as of January/February 2022.

The only true game-changer

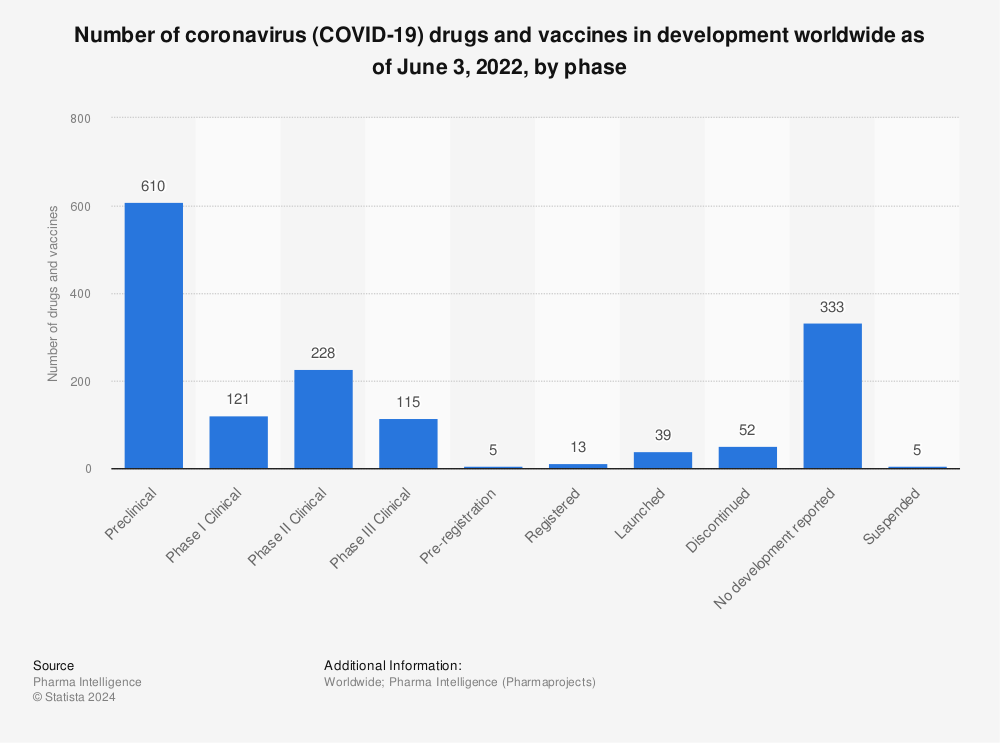

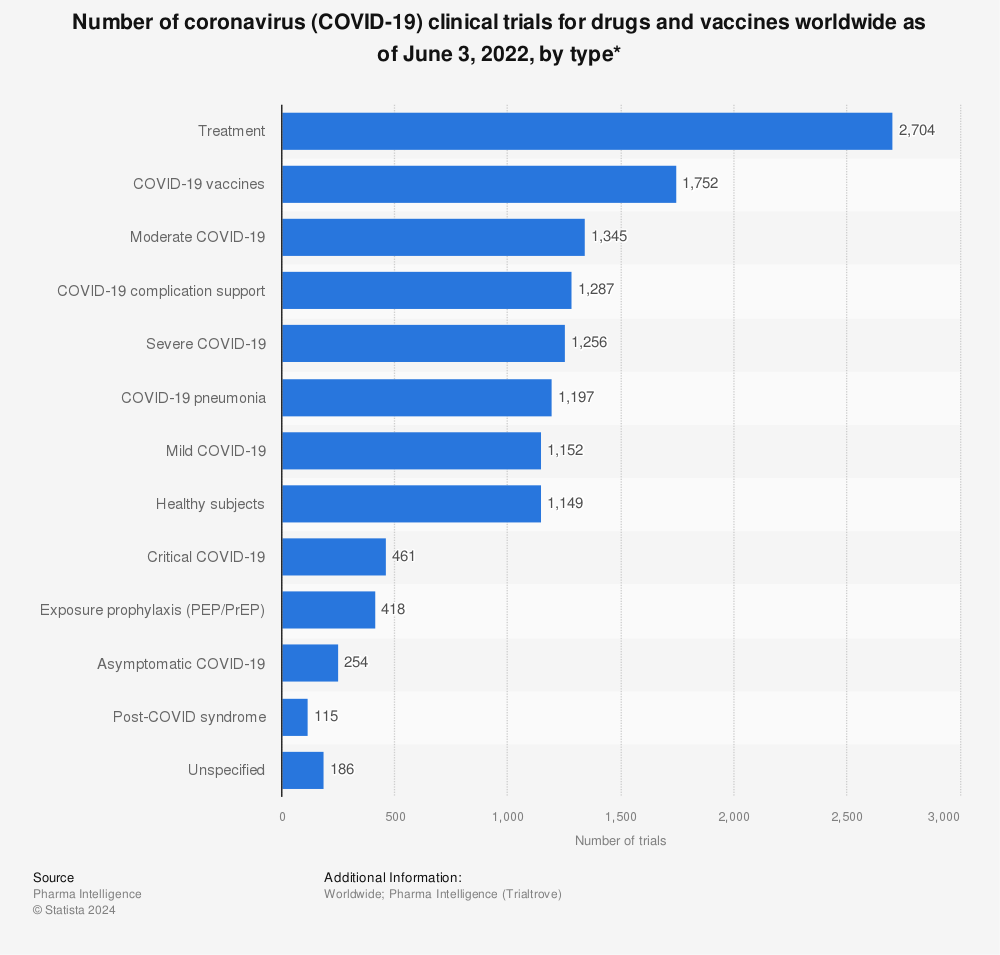

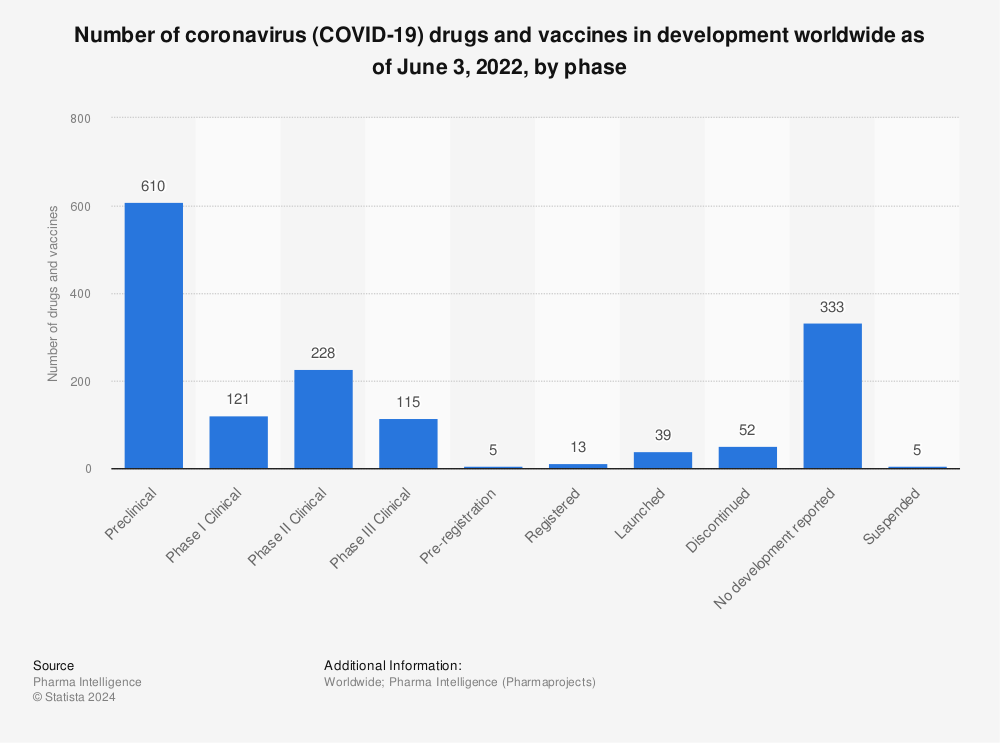

As soon as the deadly potential of the new coronavirus became obvious, finding a safe and effective vaccine was the global health priority. Other than potentially dangerous herd immunity by natural infection, for many experts it is the only true game-changer in a pandemic. Being the first company to produce a vaccine against the new disease was a matter of prestige and, of course, a matter of potentially high profits. Not only the established big pharma companies,

but also small innovative biotech firms were competing to create a vaccine against the new coronavirus. Several such companies dramatically

increased their market capitalization as a result of being involved in research on SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 - the virus that causes the COVID-19 disease).

Good news at the end of 2020

On November 9th,

Pfizer and

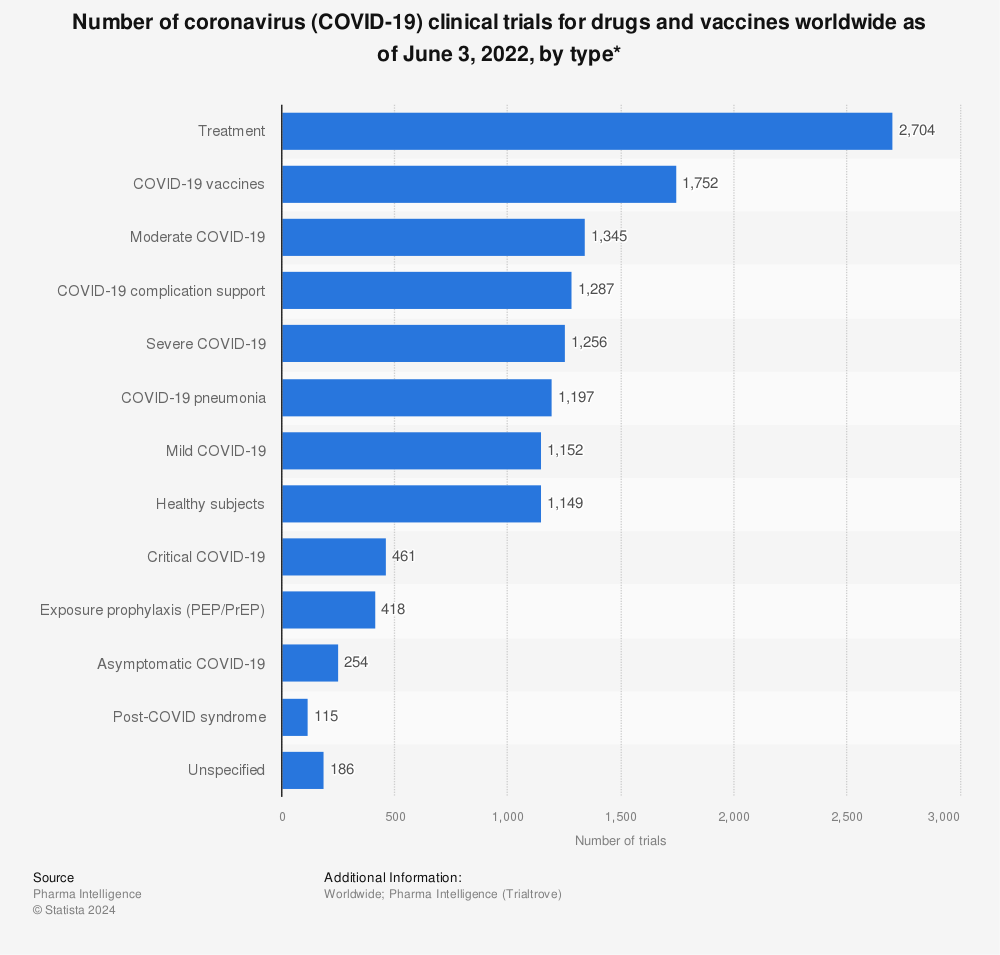

BioNTech announced that their vaccine BNT162b2 was 90 percent effective in protecting from COVID-19. After more evidence from the trials came in, the efficacy rate was corrected to 95 percent. Thus, the American-German cooperation was the first project with preliminary evidence

from phase III in clinical trials.

Only a week after the announcement of BioNTech/Pfizer,

U.S. biotech company Moderna also reported that phase III trials of its vaccine showed an outstanding 95 percent efficacy. Both vaccines use mRNA technology and were the first vaccines of this kind ever brought to market. As of early December 2020, applications for (emergency) approval were already submitted in the U.S. and in Europe. On December 2nd, the United Kingdom became the first country to announce the approval of the BioNTech/Pfizer vaccine for widespread use among its population.

AstraZeneca added to the positive news on November 23. The company reported that its vaccine – developed in partnership with Oxford University – showed a 62-90 percent efficacy in phase III. Although the efficacy was significantly lower, the vaccine was the favorite for widespread usage around the world. While the vaccines developed by Moderna and especially Pfizer need an ultracold supply chain that had yet to be established, AstraZeneca’s vaccine can be stored at normal refrigerator temperature. Therefore, it was more

attractive for remote areas and poorer countries. Finally, on December 30, the British authorities gave the green light for the vaccine.

Early frontrunners in the race for a vaccine

From the very beginning of COVID-19 vaccine research, Moderna's mRNA-1273 probably was the most mentioned vaccine in development. It was

developed by Moderna Inc. in partnership with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). Considering how slow drug development can be, the new vaccine was ready in record time, far quicker than drugs manufactured during previous pandemics. This was made possible mostly by significant scientific and technologic advances in recent years.

The mRNA-1273 vaccine was the first COVID-19 vaccine worldwide given to healthy humans. Due to the urgent situation

regulators started to grant emergency approvals for diagnostics, vaccines, and treatments. After Moderna, CanSino Biologics from China was the second company which started running clinical tests in healthy volunteers. The trio of top frontrunners was completed by a team at the

Oxford University partnered by

AstraZeneca.

A surprise from Russia

On August 11th 2020, Russia announced it was the first country to have a vaccine ready to be administered to COVID-19 patients. Scientists from outside Russia reacted with skepticism. Not only was clinical trial phase II performed with only 76 participants, but phase III results were skipped completely. Phase III began only in September with approximately 40,000 volunteers, according to Russian sources. But as of November, the first results of the late-stage trial showed that the Sputnik V vaccine had a high efficacy, ranging from 92-95 percent. While

several countries around the world have pre-ordered the vaccine, Western countries remained skeptical, stating a lack of peer-reviewed evidence from the trials in Russia. These concerns were removed to a certain extent by an analysis published in The Lancet on February 2, 2021 confirming Sputnik V's high efficacy of nearly 92 percent. A big issue for Western countries was, however, that Russia might want to gain political leverage and influence through the vaccine.

This text provides general information. Statista assumes no

liability for the information given being complete or correct.

Due to varying update cycles, statistics can display more up-to-date

data than referenced in the text.

The sudden interest in the vaccines was of course an expression of humanity’s unabated wish to eventually get back to normal life by reaching some kind of herd immunity. Nothing fueled this hope like the three most prominent/promising vaccines from Biontech/Pfizer, Moderna, and AstraZeneca/Oxford which started being approved during end-2020. Combined, these three received and agreed to pre-orders for around five billion doses worldwide.

The sudden interest in the vaccines was of course an expression of humanity’s unabated wish to eventually get back to normal life by reaching some kind of herd immunity. Nothing fueled this hope like the three most prominent/promising vaccines from Biontech/Pfizer, Moderna, and AstraZeneca/Oxford which started being approved during end-2020. Combined, these three received and agreed to pre-orders for around five billion doses worldwide.

Additionally, the enormous speed with which the laboratories developed and produced the vaccines as well as the quickened process of approval raised concerns among many people, questioning whether they had been thoroughly tested (while other major factors like technology advancements, combined forces in R&D, and the extraordinary funding from many countries were often overlooked).

Accordingly, in many countries the group of hesitant people who ‘first want to wait and see’ was significant – for example, almost 40 percent of all surveyed in the United States at the beginning of the vaccination campaign, although this percentage had decreased to just four percent as of January/February 2022.

Additionally, the enormous speed with which the laboratories developed and produced the vaccines as well as the quickened process of approval raised concerns among many people, questioning whether they had been thoroughly tested (while other major factors like technology advancements, combined forces in R&D, and the extraordinary funding from many countries were often overlooked).

Accordingly, in many countries the group of hesitant people who ‘first want to wait and see’ was significant – for example, almost 40 percent of all surveyed in the United States at the beginning of the vaccination campaign, although this percentage had decreased to just four percent as of January/February 2022.

Only a week after the announcement of BioNTech/Pfizer, U.S. biotech company Moderna also reported that phase III trials of its vaccine showed an outstanding 95 percent efficacy. Both vaccines use mRNA technology and were the first vaccines of this kind ever brought to market. As of early December 2020, applications for (emergency) approval were already submitted in the U.S. and in Europe. On December 2nd, the United Kingdom became the first country to announce the approval of the BioNTech/Pfizer vaccine for widespread use among its population.

Only a week after the announcement of BioNTech/Pfizer, U.S. biotech company Moderna also reported that phase III trials of its vaccine showed an outstanding 95 percent efficacy. Both vaccines use mRNA technology and were the first vaccines of this kind ever brought to market. As of early December 2020, applications for (emergency) approval were already submitted in the U.S. and in Europe. On December 2nd, the United Kingdom became the first country to announce the approval of the BioNTech/Pfizer vaccine for widespread use among its population.

The mRNA-1273 vaccine was the first COVID-19 vaccine worldwide given to healthy humans. Due to the urgent situation regulators started to grant emergency approvals for diagnostics, vaccines, and treatments. After Moderna, CanSino Biologics from China was the second company which started running clinical tests in healthy volunteers. The trio of top frontrunners was completed by a team at the Oxford University partnered by AstraZeneca.

The mRNA-1273 vaccine was the first COVID-19 vaccine worldwide given to healthy humans. Due to the urgent situation regulators started to grant emergency approvals for diagnostics, vaccines, and treatments. After Moderna, CanSino Biologics from China was the second company which started running clinical tests in healthy volunteers. The trio of top frontrunners was completed by a team at the Oxford University partnered by AstraZeneca.